On 14 October, Australia will vote in a historic referendum that cuts to the core of how it sees itself as a nation.

Some people think the Voice is a good idea. It means recognizing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia’s rules and making a group to give advice on their problems. They say it’s a small but important change. It helps Indigenous Australians have a proper say in their own land, even though Australia has been slow to face its history.

Others say it’s a big and extreme idea. They think it will split the country because it gives First Nations people more rights than others. However, legal experts disagree with this.

So, is the Voice really such a big change? And how have other countries dealt with recognizing Indigenous people?

The path to a Voice

Australia is a bit different from other countries that were settled by newcomers because they never made a formal agreement with the native people. They also didn’t officially acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as the original inhabitants in their main set of rules. It took until 1971 for them to be fully counted in the population, and there aren’t special seats for them in the government.

In 1962, they were finally allowed to vote in the big national elections. But for a long time, they’ve been asking for more control over their own decisions. Way back in the 1800s, leaders from the native communities were trying to have more say in their own matters. This was a tough time because of fights and diseases brought by Europeans. In the early 1900s, groups fighting for equal rights were starting all across the country.

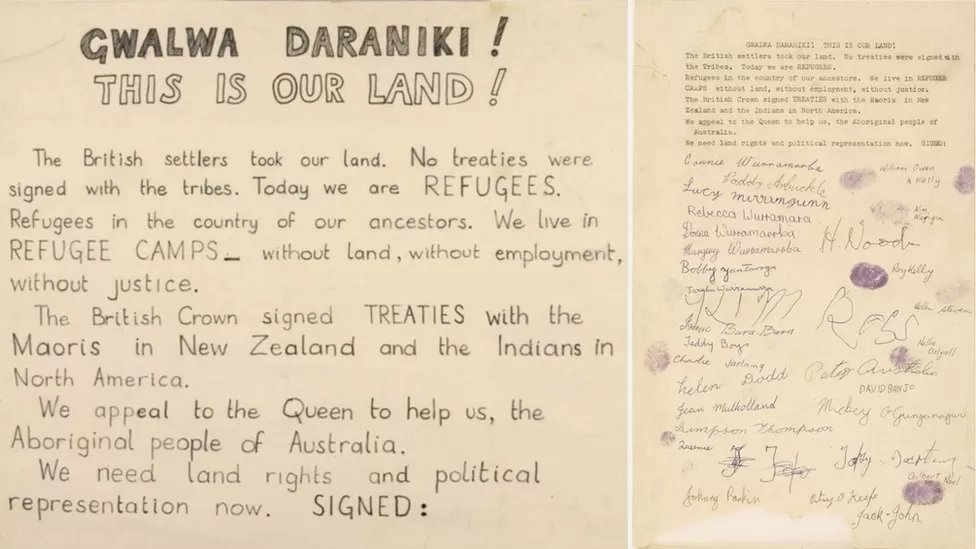

In the 1930s, a letter was written to King George V asking for a person from their own background to be in the government. Many native leaders signed it, hoping it would reach the King, but it never did.

Almost 40 years later, a request from the Larrakia people in Darwin to talk about making an agreement did reach Buckingham Palace, but they didn’t get a response.

Back in 1999, Australia had a vote to decide if they wanted to acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in a special part of their main rules. But it didn’t pass. Now, there’s a statement called the Uluru Statement from the Heart, which the Voice idea comes from. It’s a bit like the 1999 request.

This statement was written by over 250 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders from all over Australia in 2017. It asks for a group that gives advice to be made a part of the main rules. This is a step towards making agreements and telling the truth about what happened in the past.

Since the 1970s, Australia has tried making different groups of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander advisors. They were meant to help fix the big differences that First Nations communities still deal with in areas like health, money, and learning. But sometimes they had problems with the people who make the rules and with arguments among themselves, and they eventually stopped.

The people who support the Voice say that if it’s written into the main rules, it would have more power and last longer, so it won’t end up like the other groups.

‘An outlier’

The people who are against the Voice say it’s a big change and they’re not sure how it would work because there aren’t enough details. They worry that it’s a new idea that hasn’t been tested yet.

But if the change is approved, it will be up to the government to figure out how the Voice will work. They can make adjustments to it as they go along. The exact rules for the Voice won’t be written in the main rules of the country.

Some experts mention that other countries with similar histories have had groups like the Voice for a long time. For example, the Sami people in northern Scandinavia have had their own groups helping with decisions since the 1980s and 1990s. Their rights are also written in the main rules of those countries.

These groups are watched over by the government, and they give advice on how to solve problems for the Sami communities. People who support the Voice say it could operate in a similar way.

In New Zealand, when the colonizers arrived in 1840, they signed a treaty called the Treaty of Waitangi. By 1867, this treaty had set aside special seats in the government for Māori people. They also made a group called the Waitangi Tribunal in 1975 to make sure Māori folks have a say in the decisions that affect them.

In Canada, Indigenous people have rights that are written in their main rules, like having agreements and governing themselves. They also made a group called the First Nations Assembly in 1982. This helps leaders from Indigenous communities talk directly with the government.

In these countries, groups that represent Indigenous people and give advice are pretty normal and not controversial at all. They’ve been working with the government for a long time. The fact that the Voice idea is causing so much talk in Australia shows that it’s a bit unusual compared to other places in the world.

Some people who are against the Voice idea say that putting it in Australia’s main rules might give it too much power. They worry it could slow down government decisions and lead to more arguments in the courts. But important legal experts, including the federal solicitor general, don’t agree with this. They say the Voice won’t have the power to stop laws.

A really smart person in constitutional law, Prof Anne Twomey, explained that the Voice is just a way for a group to talk to the government. Any person or group in Australia can do this already. It doesn’t force the government to do anything specific.

Impacts of the vote

Changing Australia’s main rules, called the constitution, can only happen through a special vote called a referendum. In the past, out of 44 ideas to change the rules, only eight were approved. The ones that worked had support from both major political parties. However, for the Voice, there isn’t this kind of widespread agreement.

Surveys show that over 80% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people want this change. But when everyone in the country is asked, the support is going down.

The people against the Voice say that if it doesn’t pass, it doesn’t mean the fight for recognizing Indigenous people in the constitution is over. They’re talking about whether to try again with a second vote, but not everyone agrees on this idea. Some people in the ‘No’ campaign support it, while others don’t.

Some people who don’t support the Voice idea think that if it doesn’t pass, it might make it easier to talk about making an agreement in the future. But those who believe in the Voice say that if it doesn’t pass, it’s like saying no to a lot of hard work and effort from Indigenous people.

The discussion about the Voice has also been filled with hurtful words and false information, which can cause lasting harm. It’s like what we’ve seen in big elections in the US and UK recently. This makes Indigenous communities feel like they’re being watched and questioned a lot right now.

As the debate is ending, the people who want the Voice to happen are trying to convince millions of people who are still unsure. They say it’s a big chance to make history and bring about positive changes. One of the main supporters of the Voice, Noel Pearson, said that this vote is like a huge mirror for Australia. They have to choose whether to move forward or stay stuck in the past.

SOURCE:BBC